The Probable Time of Contact: Managing Risk and Resources in Fires and Intel

The Probable Time of Contact: Managing Risk and Resources in Fires and Intel

By

LTC Darrell E. Fawley, III

As ground forces seek to shape their operations and synchronize efforts in time, space, and purpose, management of limited assets becomes a critical action. Commanders in any future conflict will either face short falls in information collection assets and fires assets, or need to manage risk to the destruction of these assets. Generally, commanders assign a priority of fire and units become comfortable, based on that priority, relying on higher assets. However, commanders need to think about how they use their assets based on the point of time. To that end, Blackhorse has developed the concept of a Probable Time of Contact (PTOC) to apportion assets and manage risk.

Units consider a probable line of contact when planning their operations. This allows them to consider risk to maneuver forces and take steps to mitigate this such as changing their route, varying formations, and initiating fires. While it is right for commanders to consider the risk to their maneuver forces, their information collection and fires assets are also at risk – and likely are at a greater risk that maneuver forces. Furthermore, commanders will never have enough of either. Therefore, to ensure commanders manage risk to their assets and employ them against the most important areas, units should adopt the concept of a Probable Time of Contact that will help them apportion limited assets and manage risk.

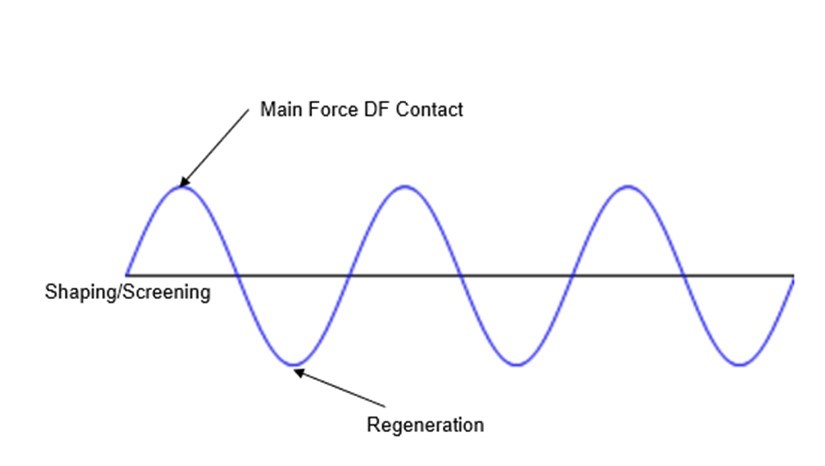

The probable time of contact is a tactical concept Task Force Battle (2nd Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry) uses to think about how to use its limited intelligence and fires assets. If we think of battle as operating on some type of wave, such a sine wave or frequency chart, then high peaks are periods of intense fighting and low peaks are periods of consolidation, reorganization, and regeneration where units are separated. Upslopes are periods leading to battle and down slopes are the movement from intense combat to culmination. (See Figure 1.)

Thus, it is possible to think of battle as having a probable time of contact meaning we can assume main force units will come into contact at a certain time.

Knowing – or fairly estimating - the PTOC enables commanders to array their assets in time, space, and purpose. For example, in periods of main force direct fire contact, priority is given to the force in contact, ensuring the maneuver unit knows “what’s on the other side of the hill” and can kill it before coming in contact. Artillery, UAS, rockets, attack aviation, etc. will be in support of the unit in contact as long as it believes it needs them. The commander focuses on giving the unit in contact the fairest chance at survival and success. However, during periods of regeneration and leading toward the next battle, the commander uses fires and intel to shape the next fight and enable decisions. Subordinate commanders likely will not receive any direct support of assets. The threshold to fire is exclusively held at the High Payoff Target List (HPTL). In those periods of shaping or screening, a steady state if you will, the commander balances priorities to ensure screening forces have assistance while also ensuring deeper shaping. The threshold to employ brigade or division fires – lethal and non-lethal - assets is high, but not limited to HPTL. Subordinate commanders may nominate targets and request assets, but the staff balances use of these assets with the deep fight.

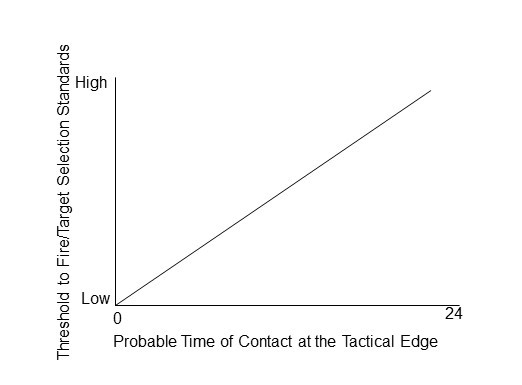

Figure 2 demonstrates the threshold to fire guns based on the probable time of contact at the tactical edge using a scale of in 0 hours (in contact) to 24 hours until main force contact. In this case, the target selection standards remain high when the commander perceives that main force contact will not happen for several hours. The commander may chose to support his or her reconnaissance assets with additional fires and intel support, but he or she trades off the ability to use these assets deeper. Otherwise the threshold to fire is high and target selection standards remain high until the likely time of contact gets closer. As this happens, the threshold to fire slides further down the line. In this construct, the focus is on apportioning limited assets.

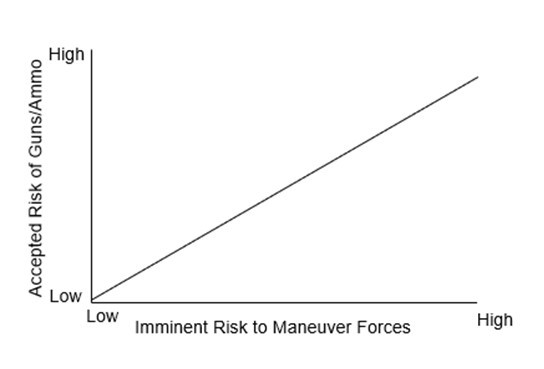

Another way to look at this is through risk, as demonstrated in Figure 3. The commander is concerned about the loss of guns through exposure to targeting and counter fire. Further, the commander has a finite amount of ammunition and that ammunition is needed for the main assault. Therefore, commanders must be cautious when contact is not imminent. However, when units are in contact, the commander risks his or her guns to keep soldiers alive, ensure the attack succeeds (or fails when in defense), and to prevent defeat.

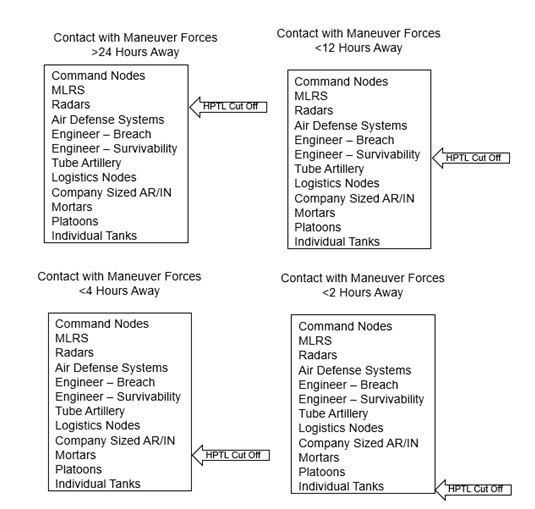

Figure 4 shows a way of thinking of this using the High Payoff Target List. As the chart shows, when contact is not imminent, the commander is only willing to fire at the most lucrative targets, shaping the battlefield with low risk to guns. As contact becomes more imminent, the commander lowers his or her threshold to fire until eventually the commander is willing to shoot at most battlefield assets and personnel in an attempt to ensure mission success and preserve lives and resources. (The HPTL in Figure 4 is a generic example and TF Battle has a different HPTL each mission based on the mission variables.)

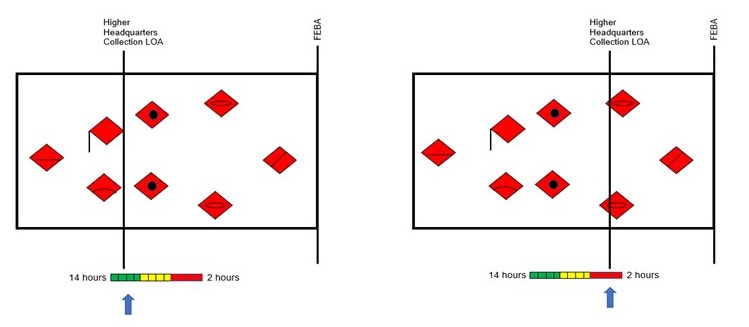

The above examples focused on fires assets, but intelligence also possesses limited assets related to requirements. Therefore, in a similar manner, the commander focuses these assets based on the probable time of contact. Therefore, the commander looks deep to shape the coming fight while contact is not imminent. For example, with contact not likely for 14 hours, the commander is looking for fires assets, air defense, and command posts. However, with contact imminent, the commander focuses on the forces close to his or her own to ensure his or her subordinate commanders have the best read. Figure 5 demonstrates this graphically. A way to visualize this is like a spring. When there is a large amount of time from now to the PTOC, the string is stretched with one end being the forward edge of the main force and the other end being the area the commander focuses collection on. As the PTOC gets closer, the spring gets more compressed until the area the commander is focusing on is almost touching his or her main force. Then, as the battle culminates, the spring stretches back out again.

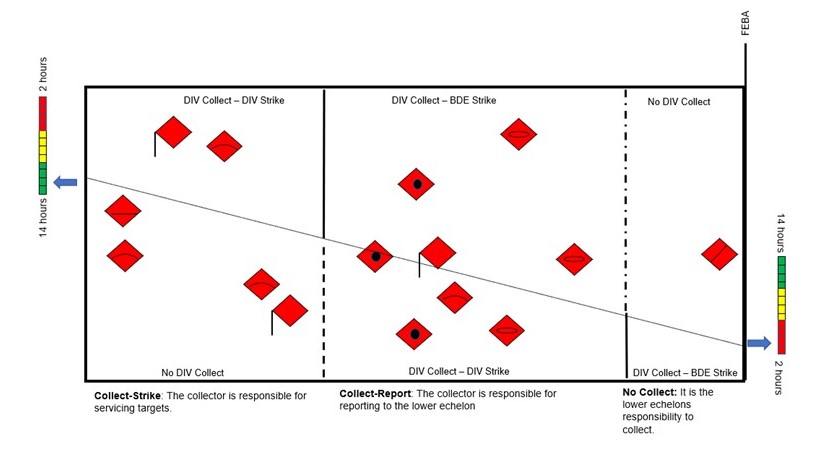

The transparent battlefield will require headquarters to get smaller and likely push intel collection higher up to division. There is tension between Division reporting and Divisio

n striking. This is a source of friction for Blackhorse. For example, the Division G2 or ACE may report a particular enemy element or system, but Division Fires does not always report striking it. This is not only a reporting gap potentially leaves targets on the table with no one feeling responsible for servicing them. There is a need to communicate across the warfighting functions in a succinct manner. In accordance with use of temporal considerations, Divisions should spend their effort collecting deep and striking deep when contact in not imminent. As the Division potentially uses assets in support of brigade collection, there is a line where it will report but not strike. There is also a line where division will not provide any assets. As the time to contact decreases, these lines shift closer and closer to the FLOT. So, while at 14 hours, the Division may be looking at the enemy’s consolidation area and battle zone, and only striking in the consolidation area, as contact becomes more imminent, the division begins to shape in the battle zone. Similarly, the BCT adopts a collect-strike, collect-report, no collect area closer to the FLOT. Figure 6 demonstrates this construct in time and space.

This essentially is a discussion about how a higher headquarters shapes the fight for the lower headquarters. Another way to think about it is that a higher headquarters works far to near. To think about this, it useful to us the example of the three-phase air campaign to open Operation Desert Storm. Using the aerial warfare theories of Colonel John Warden, the Combined Forces Allied Air Component Command attacked a set of high payoff targets initially attacking communications, air defense, and command and control sites. Over time, the bombing expanded to additional capabilities and was also responsive to the pressure of higher echelons (the political need to destroy SCUDs) and lower (the tactical desire to shape main force Republican Guard Units).

In a similar way, a higher commander uses his or her assets in the lead up to a battle based on time and distance and may arrange to hit certain targets at a time more advantageous than when discovered. For example, at times, TF Battle identifies the enemy brigade command post or battalion command posts and retains custody of the target without striking. It can be more advantageous to strike these at the time of attack. Similarly, the task force often retains custody of PAAs without striking them on initial visual contact, especially when preparing for the offense. This is where the Desert Storm analogy gives way to lessons from the desert. Hitting a PAA or command post too early may enable time to regenerate or establish an alternate means of fire or control. Instead, the task force will usually time actions based on its maneuver strikes to achieve maximum effects in terms of confusion and lost capability.

The Probable Time of Contact is a construct that has enabled Task Force Battle to apportion information collection and fires assets to align them in time, space, and purpose. It manages risk while allowing the commander to shape the battlefield and establish conditions for a successful attack or defense. Maneuver units should work with their fires and intelligence staffs to implement this construct in order to effectively employ their limited and critical fires and intelligence assets.