The Emergence of Armed Drones and Today’s Collateral Damage Problem

The Emergence of Armed Drones and Today’s Collateral Damage Problem

CPT Jonathan Henry

The use of drones in armed conflict has precipitously increased over the past 18 years since the United States declared the War on Terrorism. The armed drone made its combat debut in Afghanistan less than a month after 9/11, delivering America’s first drone strike on October 7, 2001. In the War on Terror, drones have successfully removed thousands of militants from the battlefield, recently killing General Qassem Soleimani, the commander of Iran’s Quds Force. Armed drones are very effective at killing terrorists; however, the leading objection of drone warfare is the claim that they produce excessive civilian casualties.

The resulting casualties have left many to question the moral standing of using drones. Despite this notion, evidence shows that the development of armed drones has dramatically reduced civilian casualties.[1] In reality, armed drones have become so effective that they seem to have reduced some critics’ tolerance for civilian casualties to be near zero. The evidence shows that armed drones have cut zeros off collateral damage figures.[2] Yet despite the success, the limitations of technology and the Collateral Damage Methodology (CDM) cause civilian casualties to continue to be a part of the calculus of warfighting.

There have been several policies created by the U.S. Military to reduce collateral damage, such as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction (CJCSI) 3060.01A, the No-Strike and the Collateral Damage Estimation Methodology. Despite the success of the CDM, which should not be diminished, the estimates of civilian casualties range from 2.5% to 35%.[3] As a consequence, the U.S. Military has a moral obligation and a strategic interest in further reducing civilian casualties and minimizing the effects of war. While the use of armed drones has significantly reduced collateral damage, it has not minimized it. Some of this can be attributed to the known limitations of the CDM.

Limitations of the Collateral Damage Methodology

The CDM was designed for geospatially defined targets – i.e., stationary targets, buildings, or other objects which can be reliably identified with satellite imagery. The CDM was developed as the U.S. Military was using drones to engage targets in a relatively slow-pace counter-insurgency. The CDM is not capable of adequately addressing dynamic targets as well as time-sensitive targets. The CDM does allow for the engagement of dynamic targets under a more restrictive method called Field Collateral Damage Estimation (CDE); however, it increases the risk of collateral damage. Additionally, the CDM does not account for unknown transient civilians.

Human Error and Targeting Process

When conducting an airstrike in a dynamic environment, it can be challenging to quickly synchronize all of the elements of a strike and approximate the effects of the CDE analysis on the feed of a drone. The reliance of military personnel to estimate the timing and the effects of an airstrike is a substantial limitation and introduces human error, which increases the likelihood of collateral damage. Research from the U.S. Drone program in Pakistan concluded that “reducing civilian casualties depends on the entire engagement process, including planning and training considerations, not simply the characteristics of the weapon platform.”[4] A report from the Center for Naval Analyses supports these findings and shows that the failure to mitigate the other factors in a strike, like the targeting process, resulted in an increased risk to civilians from the use of drones.[5]

Why Reducing Collateral Damage Matters

The U.S. Army is a Profession of Arms, comprised of experts who are certified in the ethical application of land combat power. One of its core responsibilities, which helps sets the condition for lasting peace, is to understand the cost incurred when conducting military operations, especially to non-combatants. Additionally, with the re-emergence of great-power competition, failing to thrive in these environments could have strategic implications. America has not seen a large-scale conflict since the U.S. Military adopted the CDM in the mid-2000s.

Considering the relatively time-consuming nature of CDE, it is hard to conceive that in such a fight, the same devotion can be given to minimizing collateral damage without degrading offensive operations or increasing risk to civilians. The same limitations that the CDM fails to address in conflicts short of conventional war would be intensified in large-scale conflicts. With conflicts short of conventional war, studies show that civilian casualties have an impact on the local population and influence their level of support for the coalition.[6] One of the implications is that in order to decrease insurgent violence, we must reduce collateral damage further as it holds strategic value. While it is not yet possible to provide the same level of protection for civilians in large-scale conflicts, future efforts to reduce civilian casualties in limited-scale conflicts are promising at increasing their protection across the spectrum of conflict.

Therefore, we must address the limitations of the CDM and also make its application more feasible for large-scale conflicts. Doing so will give the U.S. military a tactical advantage in great-power competition as the technology adopted would also increase our speed and lethality. Additionally, we must increase protection for civilians in conflicts short of conventional war in order to set conditions for peace in a way that is consistent with our professional ethics. In light of warfare, which is likely to remain dynamic, complex, and limited in scale, as well as a new era, which is being defined by great power competition, we must be able to confront the two without compromising our national values. In light of our values and the threats which challenge our national security, the following are promising at allowing the military to confront its adversaries in all threat environments while reducing civilian casualties even further.

Recommendations

Advanced Weapons

Prioritize the development and fielding of Dialable Effects Munitions to allow for increased operational flexibility and to further reduce collateral damage. Aircraft can only carry so many munitions and the flexibility of allowing the munition’s effects to be dialed up, or dialed down, increases the availability of low collateral damage producing weapons without sacrificing military strategy if a more powerful weapon is needed. Prioritize the fielding of Direct Energy Weapons (DEW), especially within UAS platforms. DEWs would allow the engagement of dynamic targets at the speed of light and with very little collateral damage as their effects are tunable. DEWs address two significant limitations within the CDM, which is its inability to account for dynamic targets as well as transient civilians.

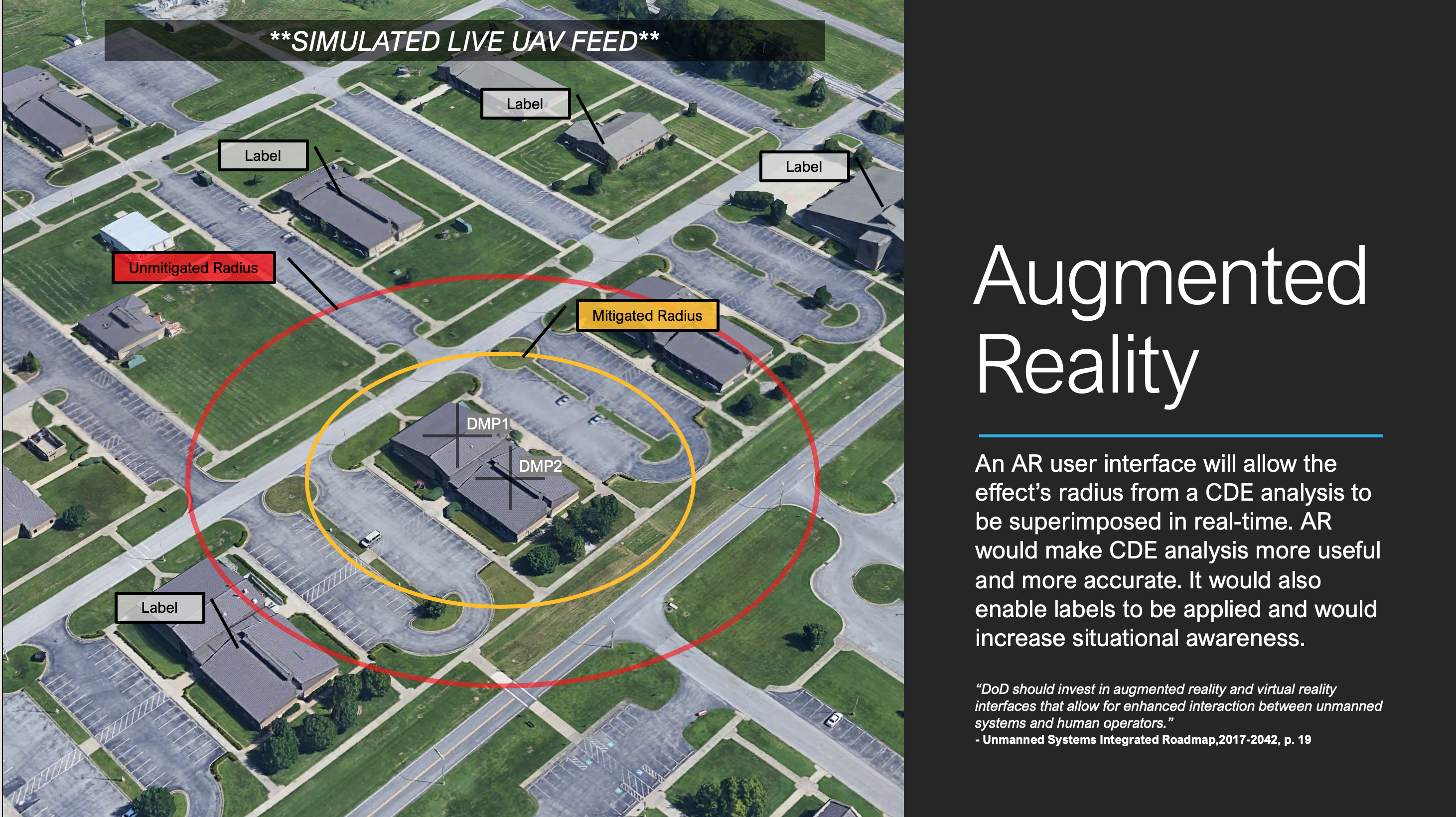

Augmented Reality

Develop an augmented reality UAS user interface that allows the mitigated and unmitigated effects radius of a CDE analysis to be superimposed over the live feed of a drone. This capability will allow military personnel to better estimate the effect's radius of the munition within the actual environment. It will offer more protection for transient civilians and improve our ability to engage dynamic and time-sensitive targets. Additionally, using augmented reality will allow geotagged labels to be superimposed. These labels could be non-strike entities, grid reference systems, friendly locations, or targets, to name a few. The DoD is already using AR and AI technology, and the Unmanned Systems Integration Roadmap FY2017-2042 outlines the development horizons for these technologies within UAS platforms.

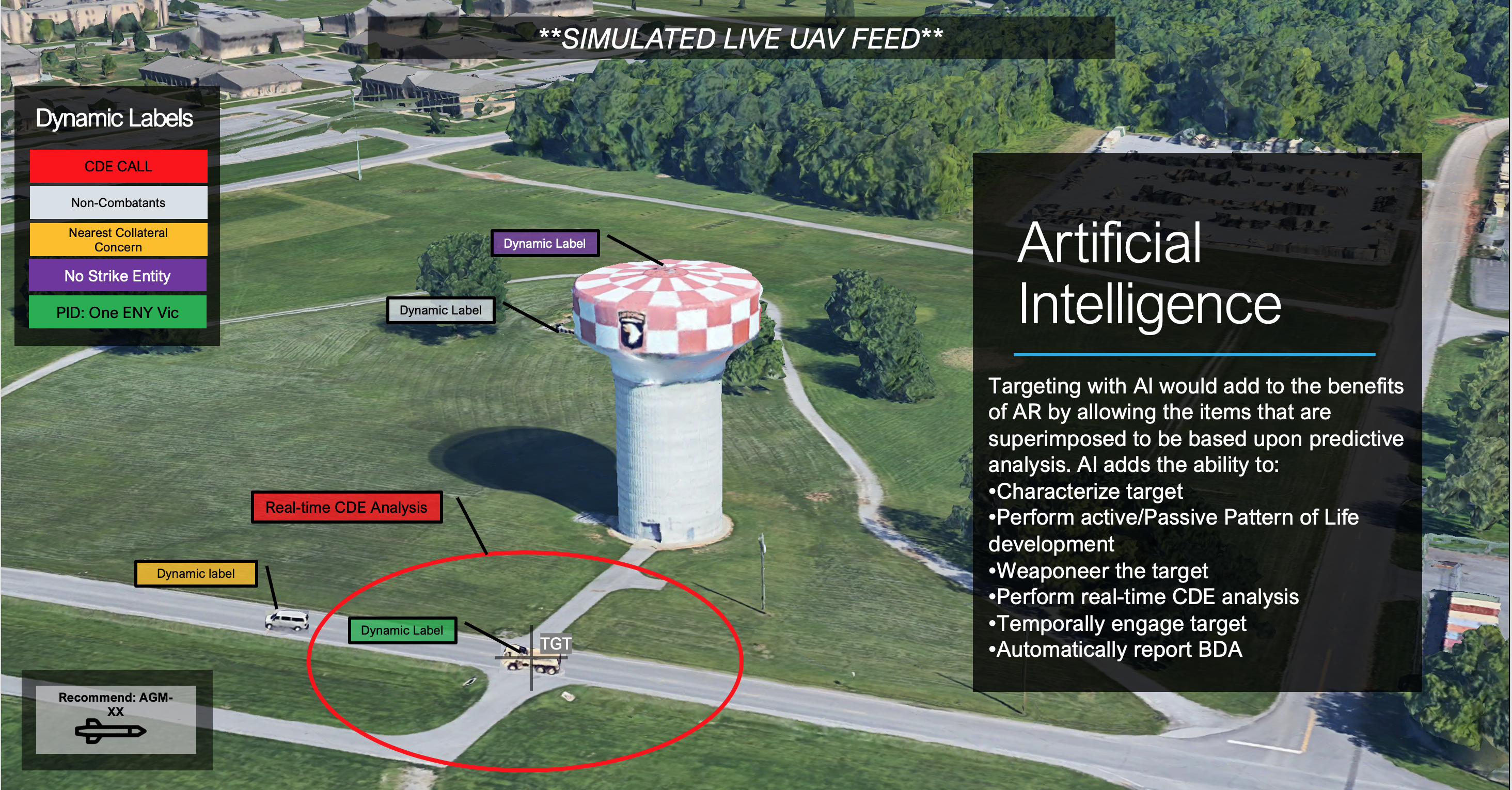

Narrow Artificial Intelligence

The use of Narrow AI in targeting is promising at reducing civilian casualties while also increasing lethality as long as its implementation is consistent with policies such as the DoD’s Directive 3000.09, Autonomy in Weapon Systems. Used in a limited and compartmentalized way, it could improve target selection, transient scans, Pattern of Life development, and allow for real-time CDE analysis. Real-time CDE would allow dynamic and time-sensitive targets to be engaged while providing the same protections as a thorough CDE analysis. This capability would allow enhanced protection for transient civilians as it would update the risk in real-time and allow for maximum flexibility in engaging targets.

Ideas, once thought to be farfetched, are becoming a reality. The Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC), is already looking at efforts to speed up fire support with AI. Work is already being done with JAIC to use AI to characterize targets with programs like Project Maven. Remember the acronym SHAT, which stands for Size, Hull, Armament, and Turret? AI could accomplish this instantaneously and more accurately. AI would be used to conduct both active and passive POL development, which would help characterize the population density of an area. The benefits are especially significant in urban environments, as the population of civilians can be significantly underestimated. Once a target is characterized, AI could help weaponeer the target to ensure the effects are adequate for mission accomplishment, but not excessive, which increases the risk of civilian casualties.

AI could be used in decision-making processes such as targeting and increase our adherence to the principles of distinction and proportionality under International Humanitarian Law. At a time when data is becoming abundant and overwhelming, turning that raw data into actionable intelligence is paramount. While much of the attention on emerging technology is its ability to increase our lethality, we should also consider how it can be used to reduce the effects of war. This is especially true with autonomous systems, whose role is likely to increase in the future considerably. Our ability to fight and win a large-scale conflict, as well as dynamic conflicts short of a large-scale war, will depend mainly on our ability to integrate and use these emerging technologies.

[1] American airstrikes in North Vietnam resulted in an estimated 65,000 civilian casualties over nine years (Hirschman, Preston, & Loi, 1995).

[2] (Anderson, 2013, p. 21)

[3] The variance is mainly due to the issue of defining who counts as a combatant. The Columbia law school estimates that 35% of the victims of drone strikes in 2011 were civilians. However, American counterterrorism officials estimated only 2.5% in 2011 (Etzioni, 2013, pp. 2-3).

[4] (Lewis, 2014, pp. 1-2)

[5] (Ekelhof, 2018, p. 25)

[6] When collateral damage causes a civilian casualty, it leads to higher levels of insurgent violence, whereas, when insurgents kill civilians, it leads to less violence. Reducing collateral damage can decrease insurgent violence because collateral damage causes non-combatants to punish the armed group responsible by sharing less information about insurgents with them (Condra & Shapiro, 2012).